Blog:

JA Use Case: Five steps to pave the way toward collaborative revenue

Collaborative growth: Working together to find your own way to sustainability and scale. Image: Pics of Trees

Collaborative growth: Working together to find your own way to sustainability and scale. Image: Pics of Trees

The JA/Collab Central forum on collaboration and revenue held earlier this spring surfaced more than two dozen examples of collaboration in action. This post examines one, an investigative report on deportations from the U.S. to Haiti, as a detailed use case of a collaboration yielding a high return.

Originally commissioned by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting (FCIR) with a grant from The Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund, the project deepened the budding relationship between FCIR and Florida public radio station WLRN. It also provided early experience in content sharing for members of the Investigative News Network. Eventually, more than 30 news organizations, both commercial and nonprofit, published an online or print version of the piece.

This use case outlines a successful collaboration that laid the groundwork for a deeper partnership that included revenue. It shows how partners worked together in different ways, explores how they may do things differently in the future, and offers examples to consider as you evaluate the structure and yield of potential or current collaborations.

Reporter Jacob Kushner had found a good story. The recent University of Wisconsin graduate was freelancing in post-earthquake Haiti, a place he knew from studies and visits while in college. Kushner had learned that one out of two Haitians being deported by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE) were taken straight to Haitian jails, although they had not been convicted of violating Haitian law. Many had only minor convictions in the United States. Jail conditions were bad enough that at least one deportee died. Kushner suspected that what he saw on the ground contradicted stated U.S. policy, as well as Haitian and international law.

Kushner pitched The Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund and the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting (FCIR). It was early 2011, and FCIR was just over a year old. Since its inception, co-founders Trevor Aaronson and Mc Nelly Torres had sought partnerships to expand the center’s reach.

Partners v. clients

The Florida Center for Investigative Reporting works with English and Spanish language newspapers, radio stations, and TV. Co-founder Trevor Aaronson constantly considers when to charge for work, when to share costs and when to give reports away. Data crunching has proven to be one FCIR service it’s easy to put a dollar figure on for clients. That means FCIR can track it as a specific revenue stream.

“Because of our capacity and the amount of money we thought we could raise, there was no way we could join the Florida media and say, here we are, we’re going to compete with you,” says Aaronson now. “We really reach our larger audiences through traditional media.”

FCIR works with local newspapers and television stations, but Aaronson thought this piece would be a natural fit for public radio. It had strong narrative elements and people who could tell their own stories firsthand. Kushner had only done a couple of audio slideshows online, but he was eager to try radio.

In its first year, FCIR had developed relationships with two major Florida affiliates of National Public Radio (NPR), WUSF in Tampa and WLRN in Miami, which is embedded in the Miami Herald newsroom. “Our very first investigation, we didn’t even have a print partner. [A Florida affiliate of] NPR…interviewed our reporter and did a story about our findings,” Aaronson remembers. “Then slowly we started escalating our types of involvement.”

By the time Kushner’s pitch came in, FCIR was deep in a collaboration with WLRN on a different story. In that case, the reporter was newly associated with FCIR but had previously freelanced for the station. In Kushner’s case, news director of WLRN-Miami Herald News Dan Grech took a chance, investing time to advise the radio novice on story approach and equipment, even though he wasn’t sure it would bring a return.

Franco Coby in a Haitian jail. This photo was used by both the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and Miami radio station WLRN in a collaborative reporting effort. Image: Jacob Kushner/FCIR

Franco Coby in a Haitian jail. This photo was used by both the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and Miami radio station WLRN in a collaborative reporting effort. Image: Jacob Kushner/FCIR“Here’s a guy, he’s obviously relatively young, who’s got this grant from this group and wants to make a radio story. And trust me, I hear this a lot,” Grech says. But the relationship with FCIR had been good so far, and Grech valued the extra depth FCIR reporting brought WLRN listeners.

“The reason why we do investigations in collaboration with newspapers like the Miami Herald or places like the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting, which are grant funded, is because they have both the legal recourses and the resources to put in to the months long work it takes to come up with investigative findings,” he says. “And my station, small as it is, is just simply not able to come up with those findings in many cases on our own.”

WLRN aired five investigative reports last year, two in collaboration with FCIR. All won national or regional awards; this story about deportees won several Green Eyeshades (pdf) and contributed to a reporting package that won a regional Edward R. Murrow award.

The first step for a successful collaboration: mutual benefit. FCIR wanted a larger audience. WLRN wanted to solidify its reputation with investigative reporting.

Paying the way

When you share a story, who pays for what? The bulk of Kushner’s costs and fees were covered by a $4,000 grant from The Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund, plus $500 from FCIR coffers. The still-fledgling Investigative News Network (INN), interested in making the story available to its members, helped out with another $500. WLRN had no financial commitment; Aaronson’s aim in that collaboration was simply to broaden the distribution of FCIR’s investigative work. Plus, Aaronson says, WLRN’s radio story was something the center just couldn’t do on it’s own.

Sharing space

Public radio station WLRN and McClatchy newspaper The Miami Herald have shared a newsroom for almost a decade, part of a deep collaboration that includes daily reporting, specials and promotion. News director of WLRN-Miami Herald News Dan Grech calls it “one of the most powerful media partnerships” he’s seen.

“It’s not difficult to ask a newspaper to pay us for a story because we just give them the story and they run it,” he says. “[WLRN] is taking our story and helping us produce a radio version of it. So they’re actually helping us create it and are more of a partner than a client.”

Aaronson did ask two INN members who were interested in localizing the story to cover Kushner’s additional reporting costs. California Watch, a project of the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR), and the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (WCIJ) contributed $750 and $1,000 respectively. Each got an exclusive profile of a person deported from their coverage area, plus either photos or a video interview. And in the end, WLRN paid Kushner $500 for extra work needed to get the right details and sound to tell the story for radio.

“One of the lessons we learned is to be very explicit about who is paying what,” says FCIR’s Aaronson.

WLRN’s Grech found value in absorbing some costs. “If you look at the actual revenue, this was a huge money losing operation for us. We did not raise any revenue around this particular piece,” says Grech. “But investigative reporting in particular has an incredibly important role in our station as part of who we are as an operation and part of the story we tell to funders and partners.”

Step two in a successful collaboration: Know the value a collaboration brings you, financially and otherwise. Does it affect your reputation? Will it build a long-term relationship? Could the partnership bring in revenue?

Editorial and legal challenges

The Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund worked with Kushner and the FCIR to focus reporting and edit initial drafts. In an email, Kushner rattles off a laundry list of guidance he received from Investigative Fund editor Esther Kaplan.

“They asked us to include more details on the crimes of certain deportees so it wouldn’t appear we were trying to downplay them; suggested we find ICE data on non-criminal detainees and those with only non-violent convictions (a request that later turned up records that led to this follow-up story); and helped us transform the issue of ICE detaining minor criminals from a brief mention into a fundamental part of the original story.”

Planned and breaking collaborative coverage

In 2009, Andy Hall, executive director of the nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism helped organize a deliberate effort for competing local media outlets to collaborate on health care coverage. “It was totally voluntary,” he says. “Each news organization retained autonomy over timing, everybody retained editorial control.” Last year, WCIJ and a local public radio station jointly broke a story alleging one state Supreme Court Justice physically attacked another. “In that case, given the high sensitivity of that story, we made sure that both newsrooms were comfortable with the version that we published,” Hall says.

The Investigative Fund always collaborates with other news outlets. Kaplan says she has learned that staying flexible is key to success. “Sometimes editors are comfortable with it being a three-way conversation,” she says. “Sometimes editors want to function as the nerve center.” When that’s the case, she’ll step away from direct feedback to the reporter, filtering her comments through the partner news outlet editor instead.

Kaplan has also learned to keep her eye on the prize of collaborative work. “Our goal is to get the good strong reporting out there and have everyone feel they got their stamp on it in the way that is most important to them,” she says.

That seems to be what happened as this story continued. When you read or listen to the four major versions (here they are: from FCIR, WLRN, California Watch and WCIJ), some editorial differences are obvious. For example, the California Watch story highlights the experience of a man from Los Angeles, while the WCIJ piece focuses on a man who grew up in Chicago and was detained in Wisconsin. The fact that Kushner had enough material to tell individual, localized stories was a big reason both organizations wanted the story, and paid for it.

But more subtle editorial differences cut to the heart of collaborative challenges. For example, the FCIR piece says the Obama administration “has not followed its own policy” of deporting people to unsafe conditions instead of seeking alternatives. WCIJ said that FCIR “found evidence” that the Obama administration hadn’t followed its policy, but, as WCIJ’s executive director Andy Hall characterizes the difference, “doesn’t bluntly assert” that as a fact. California Watch “found discrepancies” between stated administration policy and practice.

Deportees jailed in Haiti were kept locked up for as long as 11 days. FCIR and California Watch wrote that these detentions “violate Haitian law and United Nations treaties when deportees have not been charged with crimes in Haiti.” WCIJ provided more context and softened the verb, writing that the detentions, “have occurred although the Haitian constitution bans the detention of anyone for more than 48 hours without appearing before a judge, and a United Nations treaty states that ‘no one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.’”

A panel discussing this collaboration at the Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) 2012 conference characterized these different edits as “serious journalistic disagreements.” WCIJ’s Hall felt the wording in the story required careful consideration. “The initial version of the story, in my view, wasn’t fully supported by the documentation that was supplied,” he says. “We took a slightly more cautious tone.”

Meanwhile, Bob Salladay, managing editor at the Center for Investigative Reporting, which produces California Watch, says he liked the Wisconsin version better but hadn’t seen it before California Watch published. “For future collaborations, maybe we could all share the different versions,” he says. “People could read them and highlight potential problem areas.”

INN editorial director Evelyn Larrubia moderated the IRE panel. “Everyone walked away friends” from this story, she says, but she thinks editorial differences could be a growing challenge as more media outlets collaborate as equals. “You could easily see a situation where someone would say: ‘It’s my story, either run it my way or you won’t run it,’“ she says. “In this case there was a lot of goodwill because they knew and trusted each other.”

Early and often

CIR is the oldest nonprofit investigative reporting center in the country. Founded in 1977, the organization has always distributed its work through other outlets. In the past few years, CIR has started an investigative radio program, merged with a startup Bay Area news nonprofit, and continued to collaborate on high profile projects. CIR helped create the Investigative News Network, dedicated in part to “actively facilitating collaborative projects.”

Bob Salladay notes that when CIR provides stories to its partners, it also takes on the legal responsibility of libel lawsuits, as long as the stories run unchanged. Libel wasn’t a concern in this story, he says, and each news organization simply followed its own practice to fact-check, relying on the FCIR to vet of much of the reporting.

Step three: Make legal responsibilities and any editorial terms of collaboration clear in advance, but consider leave breathing room for local control. It can be an important aspect of local branding, and, if approached with care, it can build trust – necessary for any collaboration, but particularly if money is involved.

Collaboration or freelance?

In many ways, the “collaboration” on this deportee piece resembles a classic freelance success. An enterprising reporter lands a difficult story of interest to many different news outlets. He tweaks it for local markets and sells it multiple times. Indeed, Kushner, the reporter on this story, worked directly and individually with the editors of various outlets. But Kushner considered it collaborative work from day one. “INN was interested from the start, they chipped in a little funding for it before it began,” he says. “Editors caught a couple things in the editing that made us take a new look at parts of our story. The larger process certainly is collaborative, because you begin to have news outlets working together to put out content in a way that’s meaningful.”

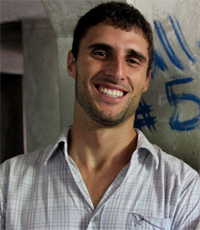

Reporter Jacob Kushner in Haiti. Image: Jacob Kushner/FCIR

Reporter Jacob Kushner in Haiti. Image: Jacob Kushner/FCIRWithout that effort, he says the story “would have been published in Florida, in print or online, and also published on the website of The Nation Institute. And that [would have been] it. Instead, this went all over the country: all over the Midwest, because of the Wisconsin collaboration, all of the West Coast because of the California one, national…because the California version got picked up by the Huffington Post and some other national outlets. So what would have been just a local, maybe statewide story instead became a highly played, very well-read national story.“

Step four for a successful collaboration: Find new ways to think about old practices.

Toward collaborative revenue

The Florida Center for Investigative Reporting is now in a broad partnership with local public radio stations in Florida. Building on the relationship developed through collaborations, including the deportee story, FCIR is a reporting partner with WUSF and WLRN on NPR’s grant-funded StateImpact Project, which in Florida is focused on education.

Aaronson says that for the first time, he and broadcast partners wrote a memorandum of understanding outlining each partners’ responsibilities. In the past, they had relied on trust and emails. The MOU identifies specific work, deadlines, payments, content sharing with other news organizations, and credit, including for awards. “Even though we have this very collegial relationship, just like any business relationship we try to make sure that everyone knows what the others are doing, and what obligations the others have,” Aaronson says.

Step five: the bottom line. Just as small amounts of money from a half a dozen news organizations can add up to more coverage than any one could buy on its own, small collaborative steps can lead to deeper partnerships, including projects that bring in revenue.

Update, July 7, 2012. This post has been updated to reflect the collaborative editing role played by The Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund.

A version of this post is published on MediaShift’s Collaboration Central. Other related posts on the JA: Resources, examples and practices to increase your yield from collaborative journalism. Costs v. benefits: What to consider as you team up. From the frontlines: Takeaways from a live chat with two seasoned collaborators. Plus the forum itself, and as captured with Storify.

Weigh In: Remember to refresh often to see latest comments!

0 comments so far.